Explore your options

Get a 100% confidential and complimentary business valuation.

Inventory is a seemingly simple concept. It’s the physical things that businesses sell to customers. However, as any business owner will tell you, it’s important to manage inventory closely. Poor inventory management can lead to foregone revenue as a result of unmet demand, or, on the other end, excess inventory can be a costly drag on your business (especially if said inventory has a shelf life!).

But inventory doesn’t just matter while running a business–it also matters when selling a business. How inventory is treated can have a meaningful impact on the outcome of a deal. We’ll walk you through all things inventory: the definition, valuation methods, and considerations when going through a business sale.

What is inventory valuation and why is it important

Inventory valuation is how you represent the value of the goods a business sells or manufactures. Inventory not only includes the finished products but the raw materials used for production.

Take the example of a custom boot store. Inventory would encompass everything from the raw materials (like leather, thread, and rubber) to the packaging (such as cardboard and glue) to the cost of the bootmaker’s labor. Note: most valuation methods include direct production labor but exclude indirect expenses such as marketing and distribution.

Inventory is important for a number of reasons:

It’s the set of inputs that will likely continue to be important for generating cash flow. These can be viewed as a set of necessary costs on the balance sheet, or as an opportunity for improvement under new management.

It impacts the value of a business. For the bootmaker, it’s clear that materials matter. All else equal, the bootmaking business with a backroom overflowing with rare leather is going to be worth more than the place using synthetic materials.

At the end of the day, inventory enables cash flow. Cash flow is ultimately what matters when running (or selling) a business.

Methods for valuing inventory

There are several popular methods for valuing inventory: First-In, First-Out (FIFO), Last-In, First-Out (LIFO), Weighted Average Cost, and Specific Identification. We’ll dive into each of these in greater detail, but at a high level, they’re accounting frameworks used for determining inventory value.

But first, COGS

COGS stands for Cost of Goods Sold and it’s an important metric to understand before walking through the different methods of valuing inventory. Cost of Goods Sold is so important because it allows you to calculate profitability. The formula for COGS is used to express inventory changes:

COGS = (Beginning Inventory + Purchases Made) − Ending Inventory

If you have a full store room at the end of the accounting period, it means you didn’t sell much. And if you have no inventory left (Ending Inventory = 0), you maximized your Cost of Goods Sold for the period.

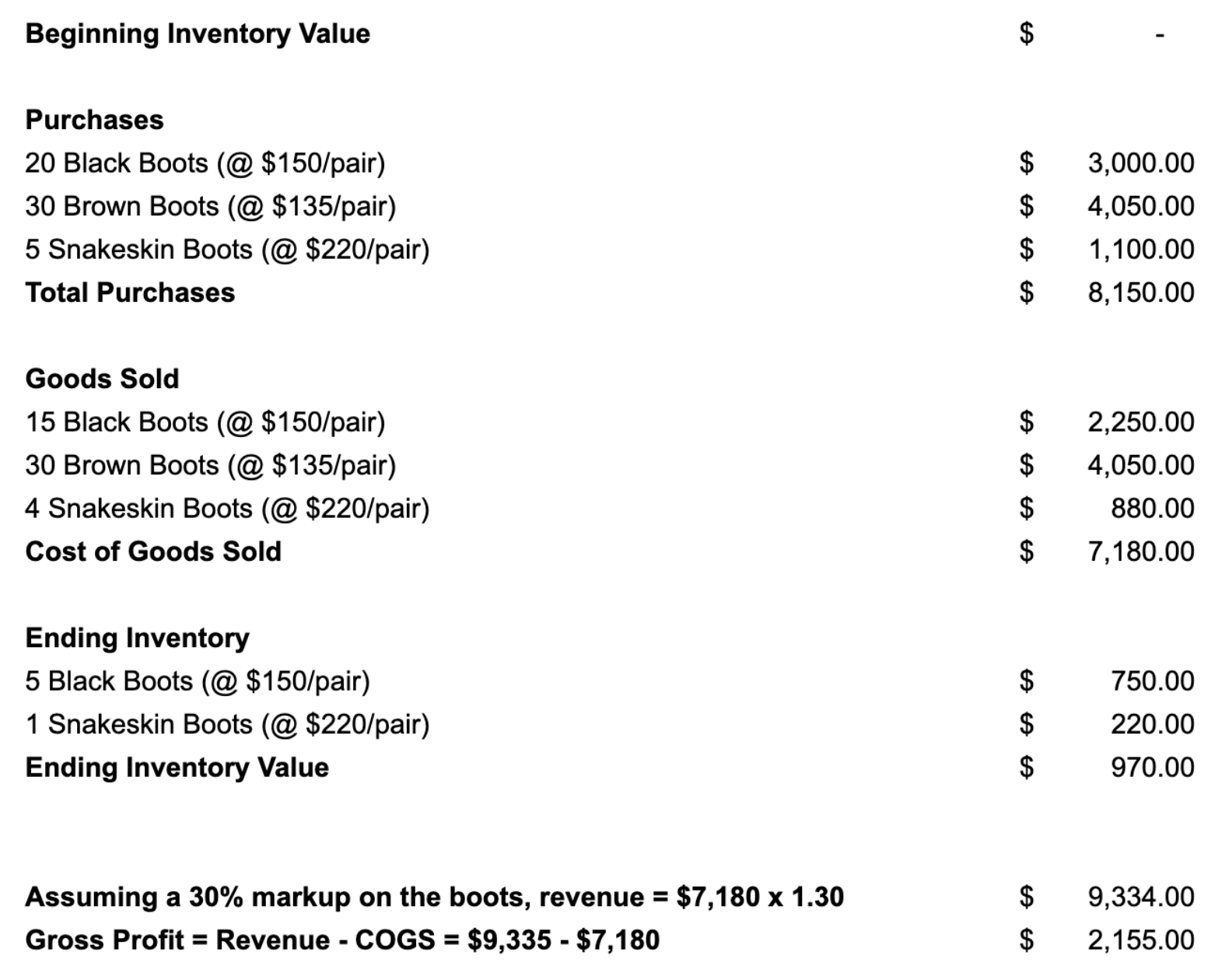

Back to our bootmaker example, let’s take a look at a simplified version of their inventory (you can think of "Purchases" here as the cost the bootmaker incurred to produce the boots). We'll also go ahead and tack on a healthy margin of 30% to calculate revenue.

In this example, the bootmaker turned a nice profit and ended the period with a little inventory leftover. This ending inventory will be applied as beginning inventory for the next period and the business continues.

Now that we have a sense of what COGS stands for, how it’s calculated, and why it matters (Profit!), let’s go into the inventory methods that use this metric.

First-In, First-Out (FIFO)

First-in, first-out is the inventory method that stipulates that the first inventory purchased by a business is also the first to be sold. Whether this behavior actually occurs or not (and in the case of your local grocery, we hope it does) is not what’s important. Being accurate and consistent with your accounting is what matters for buyers and our friends at the IRS no matter which method you use.

The benefit of first-in, first-out is that it’s the model that maximizes profitability. Since the cost of goods typically rises over time due to inflation, calculating profitability against your first expenses tends to produce the largest spread.

Let’s say the first 15 pairs of black boots cost $150/each and the next 5 cost $175 each due to the rising cost of leather. In FIFO, you would assume a cost basis of $150 for each pair of black boots until inventory has been exhausted for the quantity at that cost.

That lower cost basis is what makes this model the most profitable. But, as with most things, Uncle Sam will want his cut. FIFO is also the model that typically leads to the most taxes.

Last-In, First-Out (LIFO)

Now that we know the FIFO method, it’s time to introduce FIFO’s brother, LIFO. As you may have guessed, the LIFO method states that the most recent inventory is the first to go. The LIFO method would assume that the 5 black boots produced most recently at $175/pair would be the first out the door.

This means the LIFO method yields the lowest gross profit because the cost of goods sold is based on the most recent (and most likely to have gone through inflation) inventory bundle. This method makes the business adopting it look less profitable for that accounting period, but it also leads to a lower tax burden.

Weighted Average Cost

If FIFO is the flashy eldest sibling and LIFO the youngest child, then Weighted Average Cost is the middle child. Weighted Average Cost takes the total cost of inventory for a given accounting period and spreads it across inventory units. The equation is:

Weighted Average Cost Per Unit = Total Cost of Goods in Inventory / Total Units in Inventory

This method is commonly used in commoditized businesses where the inventory is known and consistent. It’s relatively easy to calculate and allows the owner to straddle somewhere in between FIFO and LIFO in terms of profitability and taxes.

Specific Identification

Under this method, calculations are done at the individual item level. The cost of the item persists from the time it is stocked and the revenue is calculated as soon as that specific item is sold. The key requirement for this method is the ability to track at the item level. For commoditized businesses, Specific Identification may not be worth the tracking overhead.

The benefit to Specific Identification is that it’s an incredibly accurate method if you want to understand the nuances of your business down to the item. This type of modeling could make sense for businesses with relatively unique inventory as Specific Identification can provide rich business insights beyond profitability.

For instance, maybe those teal rhinestone boots aren’t resonating with the market. Specific Identification would make this clear because those boots would show up as a mere $2 gain after collecting dust for months and undergoing several price cuts.

Which inventory valuation method is best?

The thing that really matters (for your business and the IRS) is that you stick to a method. At Beacon, we typically see businesses using the FIFO method. The FIFO method maximizes your business’ profitability on paper and sometimes leads to a higher valuation. However, you’ll have to pay your way as higher profitability means you’ll pay more in taxes.

If minimizing taxes is your primary objective, then LIFO is the method for you. Just know that what you gain in tax advantages you sacrifice in profitability. If your business is commoditized, Weighted Average Cost can be a simple way to represent your inventory. If inventory insights are the most important thing to you, Specific Identification will provide you with the most rigorous view of performance. But there will be some serious tracking involved to access these insights.

Ultimately, you need to decide what matters to you as an owner. Is it profitability? Tax minimization? Ease of accounting? Rich business insights? Hopefully, you have a better understanding of the pros and cons of the different methods. But what matters most is that you’re consistent with your method and crunch the numbers regularly.

Common objections from buyers

A lot of buyers approach financials with a certain amount of skepticism and inventory valuations are not immune. In fact, inventory is likely to be looked at fairly closely as it's such an important characteristic of the business.

If the buyer is an add-on buyer (or has accounting experience in the industry) he or she will likely have a preference for how inventory is modeled. If your method doesn’t match that preference, don’t be surprised if you get asked for a “translation” during the due diligence period.

You may also be asked questions about normalizing inventory since buyers will want to get a sense of whether the COGS they currently see on the books are expected to hold under new ownership. Let’s say the cost of boot glue spiked due to supply change issues and the current owner is trying to sell the boot business without a drop of glue left in the shop. This is something the prospective buyer would want to know as they’d need to bear the cost of the expensive glue to operate the business. Put another way, if inventory were normalized, it would be clear that COGS would increase and profitability decrease.

How Inventory is Treated in a Sale

There are three schools of thought with regards to inventory in the sale of a business:

No money should be paid for inventory as inventory is encapsulated within the overall performance picture where things like cash flow and seller's discretionary earnings reign supreme. This is not to so say you won't get plenty of questions about inventory at the negotiation table.

Only inventory in excess of net normalized levels should receive an additional payout on top of the value of the business. This is to say the buyer should only pay extra for inventory if there's inventory in excess of what is needed to run the business.

Inventory should be tallied up and included as one of the important assets in the asset sale of a business. In an asset sale, assets are calculated separately and then summed together to produce the sticker price of the business.

Here at Beacon, we typically do not see inventory valued separately. That's because we see a lot of businesses designated as a going concern, meaning they're expected to continue to cash flow immediately under new ownership. The exception is when the current owner made an outsized inventory investment and has levels well in excess of what's normally used to run the business. That's why we're proponents of understanding normalized inventory levels so adjustments can be made accordingly.

How we help

Not only are we familiar with the various methods of valuing inventory, but we’re also familiar with the living, breathing, businesses these models represent. We’re also strong translators when it comes to the various accounting languages you may encounter in the small business world.

Whether you’re a flower shop, a cabinet installation business, or a custom boot shop, chances are we’ve seen your type of business (and the buyers who go along with it). Reach out. We love chatting with small business owners!

Explore your options

Get a 100% confidential and complimentary business valuation.

Anthony is the Marketing Lead at Beacon. He previously spent his career working for software companies in Silicon Valley but is now focused on making it easier to buy and sell Main Street businesses. Anthony studied Economics at Brown University and resides in Austin.

Information posted on this page is not intended to be, and should not be construed as tax, legal, investment or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax, legal, investment and accounting advisors before engaging in any transaction.

Calder Capital

Sam Domino