Interested in buying a small business?

Subscribe to our Listing Alerts for early access to new listings.

From a high level, there are two common ways that a business owner exits his or her business. He can shut down the business, lay off the employees, and sell or auction off the equipment. Or, he can keep the business running and sell the business as a going concern.

It’s similar to buying a used car on Craigslist vs. renting a car from Hertz.

In the first instance, the buyer will pay a price close to the price of the car on the used car market. He or she will not expect much from the old owner. The car likely needs new tires. There will probably be old oil in the chamber, which needs a change. There may not be much gas in the tank. But, the buyer is getting the car on the cheap and is taking on ownership.

In the second instance, the buyer is paying the going price for driving a working, well-kept car a certain distance. The buyer expects that the rental car company has changed the oil and topped up the gas before he or she drives off the lot. And, when the buyer returns the car, the agency expects him or her to fill up the gas as well, because after all, the next renter will expect a full tank of gas as well.

Similar to a business sale, the seller of a used car only makes the price of that piece of equipment, whereas a car rental agency makes well more than the sales price of the car it’s renting out.

Turning our attention back to small business sales, working capital is to small businesses as gas and oil is to a car. It’s the lifeblood that allows the small business to operate. It may be hard to see quickly from the outside, but without it, the business would grind to a halt: unable to pay suppliers, make payroll or invest into equipment improvements.

What is Working Capital?

Working capital is the amount of money needed in the business to smooth out operations. For instance, most firms need to pay employees every other week. Most firms need to pay vendors and suppliers before delivering goods to their customers. Some customers may pay promptly or even earlier than the due date, while others may wait until the last second or pay late.

It would be near impossible to line up all of your expenses and revenue to be on the same day. So what do owners do? They use working capital to allow the business to operate.

Where does working capital come from?

Working capital can come from three sources:

Accrued profits – Most owners leave some of the profits in the bank account to serve as working capital. Because working capital can be an intimidating topic, most owners refer to this as their “rainy day” fund, without knowing that they’re actually using it day-to-day.

Owner investments – At the beginning of the business, most owners will invest their own capital to kickstart the business. As the business grows, they may find that sometimes they need to put a bit more money in to keep it running.

Banks – Banks will offer term loans and lines of credit for business owners to use as working capital.

How do you calculate working capital?

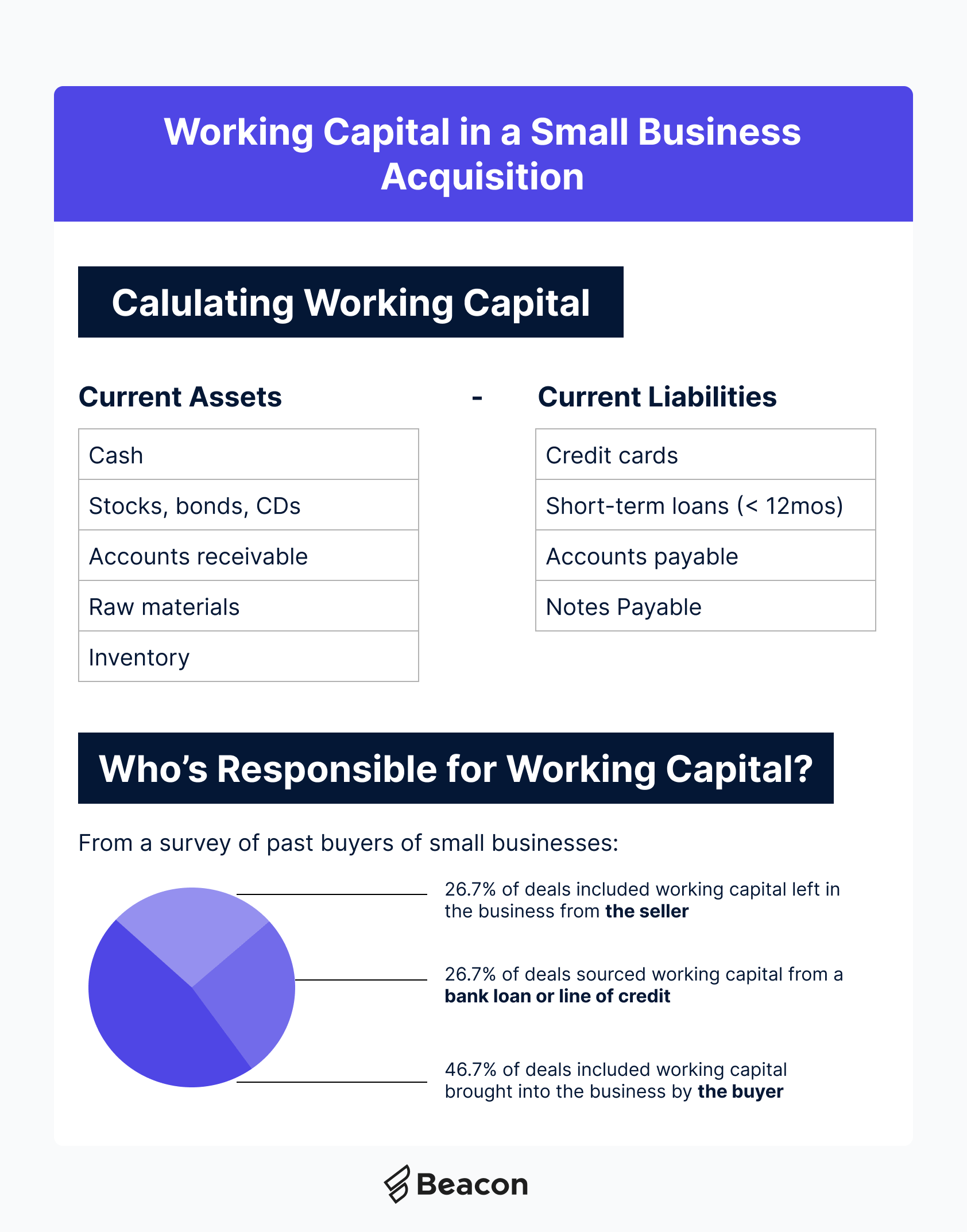

The most common measure of working capital, especially in a small business sale, is net working capital (NWC). Net working capital is calculated by taking the current assets and subtracting them by the current liabilities.

Current assets are short-term assets. The best test of whether an asset is considered “current” is whether you could quickly convert it to cash. With that lens, assets such as cash (duh), stocks, bonds, accounts receivable, short term loan advances, raw materials, works-in-progress and inventory are all considered current assets.

Current liabilities are, you guessed it, short-term liabilities. The best test of whether a liability is considered “current” is whether it’s due in less than a year. With that lens, liabilities such as accounts payable, deferred revenue, credit cards, and short-term loans.

Because net working capital may change over time in a business, the best way to calculate it is by looking at monthly balance sheets over 12 months. This helps you ensure that you’re accounting for seasonality, lumpiness of revenue, etc. After you calculate net working capital for each month in the range, you can average the net working capital to find a good proxy for the amount of working capital that the business requires. At this point, you’ll have a good sense of how much money is tied up into the business in order for it to operate.

How does working capital vary by industry?

Working capital varies by the type of business. For instance, a restaurant gets paid pretty quickly by customers, but it may have to outlay a decent amount of cash for raw ingredients. On the other hand, a manufacturer will have a lot of inventory and may not get paid until NET-30 by its buyers.

Understanding how cash is used in your business will help you identify ways to build a more efficient business and ensure you have enough current assets on hand to cover the “lumpiness” of life.

Why does working capital matter to a buyer of a small business?

When someone buys a small business, they’re typically purchasing the business with a combination of equity and debt. In other words, they’re investing a material amount of their personal savings and retirement funds, while taking out a personally guaranteed loan. They want to succeed in transitioning into the ownership seat of the business.

Given that they have a lot on the line, they want to make sure that they have enough cash to get off to the races. Oftentimes, less experienced buyers ask about working capital in a round about way: How much money do I need for the first 30 days? What are the minimum costs for the first month? How much work-in-progress is already in flight?

In other words, before the business starts to earn revenue under the new owner, how much costs will be due?

Ensuring that working capital is accounted for helps buyers avoid a scenario where they run out of gas while leaving the dealership lot.

Who’s responsible for the working capital needed to acquire a small business?

Once both parties understand the importance of working capital and what the average needs of the business are, the last question is who’s responsible for making sure there’s sufficient working capital in the business when the buyer takes over.

While the terms of working capital are up for negotiation, at Beacon most of the time the buyer brings his or her own working capital into the business and the seller leaves with the working capital that they put into the business.

That being said, the answer to who brings in working capital varies by deal size. For deals over $1M, it’s more common for the seller to leave some working capital in the business. For deals below $1M, it’s more common for the buyer to bring working capital into the business through a personal injection of cash or bundling a working capital into their acquisition loan.

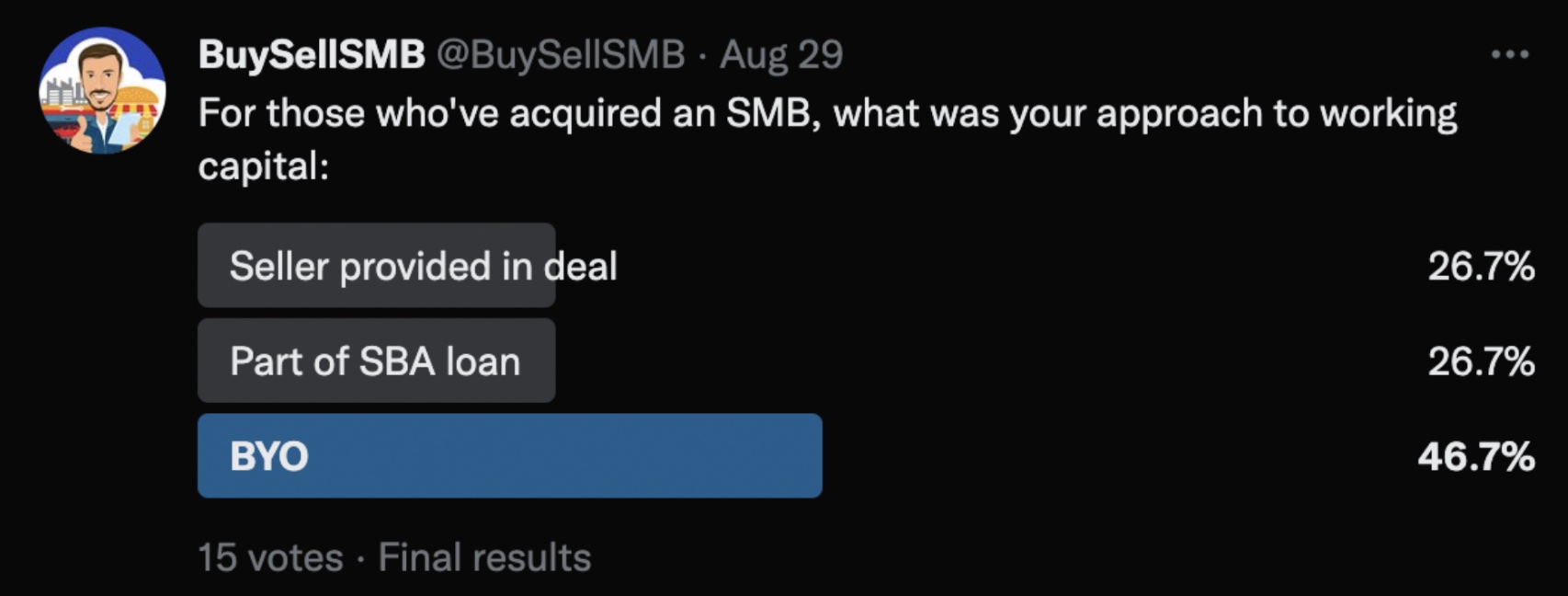

In a recent Twitter poll online, @BuySellSMB showed that nearly half of buyers brought their own working capital into the business, while around a quarter negotiated for the seller to leave working capital in the business and another quarter bundled it into the loan.

Whatever your preferred method, the important thing is to secure working capital during the handoff of the business and continue to monitor as you operate. We're here to help if you want advice on how to calculate or source working capital for your business!

Interested in buying a small business?

Subscribe to our Listing Alerts for early access to new listings.

Will founded Beacon with the mission to help the current generation of owners to retire while enabling the next to unleash their entrepreneurial spirit. He comes from a business background having graduated from the Wharton School with a B.S. in Economics.

Information posted on this page is not intended to be, and should not be construed as tax, legal, investment or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax, legal, investment and accounting advisors before engaging in any transaction.

Calder Capital

Sam Domino